blog

ICE Batteries And EV Batteries

Anybody who’s left the lights on in their car overnight or helped a mate push-start a sulky ICE vehicle knows only too well that all cars have batteries, not just EVs. So you might be wondering about what the big deal about battery life and battery fires and battery range is all about. To understand this, it’s time to go back to basics and to look at what a battery is and how it works.

Your bog-standard battery in an ICE vehicle is a lead–acid battery – the lead is why it’s so heavy, and the acid is why the batteries are “interesting” to dispose of, as the acid in question is often H2SO4 or sulphuric acid. Car batteries were a very welcome replacement to the old-fashioned method of getting the motor started with a crank handle. These lead–acid batteries are rechargeable, as the petrol or diesel motor handily charges them back up. This is why you can drive for hours and hours with the headlights on at night without the battery going flat, but if you leave lights on overnight, it will go flat.

In a lead–acid battery, both the anode (the bit that produces the positive charge) and the cathode (the bit that produces a negative charge) are made from lead and lead dioxide, respectively. The electrolyte (the bit that gets the electrons flowing thanks to chemical reactions) is sulphuric acid. Hook this up to a circuit and the electrons whizz around it in an attempt to get into balance, creating electrical current that we can use to, say, create a controlled explosion to power a vehicle. Most batteries also contain separators that stop the anodes and cathodes touching each other, which can happen if dendrites (branching crystals) start to form. If you want to get really technical, a battery is made up of a lot of individual cells containing an anode, a cathode and the electrolyte. In fact, that’s why a battery is called a battery – it reminded the early inventors of an array of cannons or other weapons ready to fire. The batteries can last for years, especially if turned over regularly and cared for properly (and that’s another subject for another day).

The basic design of a lithium-ion battery (LIB) inside an EV is similar. It’s got an anode, a cathode, an electrolyte and a separator. In this case, the cathode is made from more exotic metals and oxides, such as lithium cobalt oxide, lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide and lithium nickel cobalt aluminium oxide (try saying that quickly!), and their conductivity is improved by mixing them with conductive black carbon. The anode is usually made of graphite. The electrolyte has more lithium, specifically lithium salts dissolved in organic solvents that have plenty of the lithium ions that give the batteries their name. These batteries are a lot lighter than lead–acid batteries and can deliver a lot of punch. They also have a longer lifespan than other types of rechargeable battery, such as ni–cad (nickel–cadmium) batteries and don’t have the problem of “memory”.

The problem with lithium batteries is that the electrolyte is very, very flammable. The lithium is also prone to growing dendrites, which can cause short-circuits (and thus fires), especially if it’s charged too fast, overcharged or charged at too low a temperature. Lithium also gets prone to throwing a dramatic wobbly if it gets too hot or if the battery is damaged. It’s a case of the lithium’s strengths – its unstable chemistry that allows it to generate a charge – being its greatest weakness.

Lithium-ion batteries haven’t been around for as long as lead–acid batteries, as they only came on the scene in the 1960s and were popularised by Sony in the late 1980s. The lead–acid battery, however, has been around since the 1880s. In other words, it’s early days for lithium-ion batteries, and they’re working hard to improve the batteries and make them better.

But what happens when the batteries come to the end of their lives, which is inevitable? This is more of an issue with lithium batteries, as lithium is a much rarer metal, whereas lead is pretty common and humans have been playing around with it for millennia, although it’s now not used as much in common products (except for batteries) because of the health hazards.

The good news is that both types of battery can be recycled. It is possible for both metals – lead and lithium – to be cleaned up and used in new batteries. In fact, if you have an old battery of either type, then the best thing to do is to take it down to your nearest recycling centre and get it dealt with. Otherwise, both types can be a bit nasty, although the nastiness of lithium is more dramatic (fires) than that of lead (slow poisoning). Most lead in the batteries can be recycled; once again, the rate of recycling of lithium is a bit behind, most because it’s still a young technology. The acid inside a lead–acid battery can easily be neutralized or put to other uses, including making fertilizer.

4WD and AWD

Getting the best grip on the road or terrain is what will get you moving forwards from A to B in the shortest time. Ever since the invention of the first cars, two-wheel-drive has been the mainstay for delivering the engine’s power out to the wheels. At first, two-wheel drive was usually via the rear wheels, as it was much simpler to run a drive shaft from the engine at the front of the car back to the rear wheels to get grip from the rear wheels and to let the front wheels have the job of steering the vehicle.

In saying that, there is also history of 4WD being experimented with back as early as the late 1800s in combination with a traction engine, and, of course, in World War II, the 4WD Willys Jeep was a game-changer.

Once mechanical engineering and quality improved over time, the concept of having the engine over the front axle and the front wheels as the driving wheels as well as for steering the vehicle lowered production costs. A combination of rear-wheel-drive and front-wheel-drive cars were available as a matter of course right up to the 1970s and 1980s. Through the 1990s up until the present day, it was more common to see front-wheel-drive cars for everyday driving.

However, it was the 1980s that proved to be a very innovative period in automotive design and mechanical engineering. The greatest advancement in road-going cars was arguably the use of four-wheel-drive to establish greater levels of grip. As racing and supercars demanded faster cars, the need to control all that power (and actually make better use of it) was essential for winning, especially as there was an ever-increasing number of high-performance cars being pulled out of roadside hedges or being wrapped around power poles.

Enter Audi. Audi’s Quattro technology marked a significant moment in high-performance cars’ and supercars’ history. The Audi Quattro’s technology was essentially the dawn of the modern supercar’s 4WD system, and when Audi entered the World Rally Championship in 1981 with their Audi 80 Quattro car, they were unbeatable. The second-place car was over twenty minutes behind the race-winning Audi!

What is the difference between 4WD and AWD?

This is a good question to answer, because there are numerous new cars of all shapes and sizes available with AWD or 4WD. Generally speaking, four-wheel-drive (4WD) is the older off-road system that has the power split 50:50 front to rear. Add a diff-lock into a 4WD system, and these are off-road kings. Four-wheel-drive can be disengaged so that just two-wheel-drive (2WD) can be used on easier terrain, including for when you’ve finished your off-road adventure and you just want to head back home on the tarmac with 2WD only.

The basic principle of an all-wheel-drive (AWD) system is that it can deliver the optimum level of torque to each wheel individually, thus giving the best possible drive and traction. AWD systems tend to be permanently engaged, but with the power split front to rear, along with individual wheels being variable according to what each wheel is sensing and therefore demanding at the time. AWD systems are more complex in that they use sensors which send precise information and values of each wheels’ speed, torque, wheel slip/spin, brake pressure, and steering input to the AWD’s central control system. The control system then adjusts the torque supplied to each wheel.

Land Rovers and many other new serious off-road vehicles use AWD systems with various diff-locking abilities, which also make them real off-road kings. Four-wheel-drive systems are simpler in nature and are thus simpler and cheaper to fix than more complex AWDs. That said, many manufactures like Subaru know how to make solid, dependable AWD systems for their cars and SUVs that are mainly aimed at everyday on-road use and trips up to the ski fields, but with the credentials for performing well even in some fairly serious off-road terrain.

If you live in a part of the world where gravel roads and rainy seasons collide, then an AWD vehicle with decent ground clearance should be parked up your driveway. If your day includes a trek out to the building site, feeding out to stock, or traversing any serious off-road terrain, then a heavy-duty 4WD or AWD vehicle will be your companion. The good news is there are plenty of these sorts of vehicles about, many of which can be bought new at a good price via Private Fleet.

New South Wales and New Zealand: Spot The Difference

Thinking of heading across the ditch to New Zealand this winter for a spot of skiing or sightseeing, picking up a rental car so you can travel according to your own fancies? If you’re heading over from New South Wales, you’ll find that although a lot of things are the same when driving in New Zealand compared with back home, there are quite a few sneaky little differences that might trip you up. Most of the road rules and road signs will be familiar, but some aren’t and some are nonexistent. Here’s a handful of some differences you might notice:

Even in the middle of what passes for a city, there’s way less congestion. In the busiest parts of town during rush hour, you’ll get some congestion, but nothing like you’ll find in the middle of Sydney.

People don’t honk the horns half as much. OK, someone might honk if the driver at the front of the queue is naughtily on their phone or daydreaming and doesn’t notice that the light has turned green, but drivers seem more patient in, say, Christchurch than they are in Sydney and will jump on the horn a lot slower.

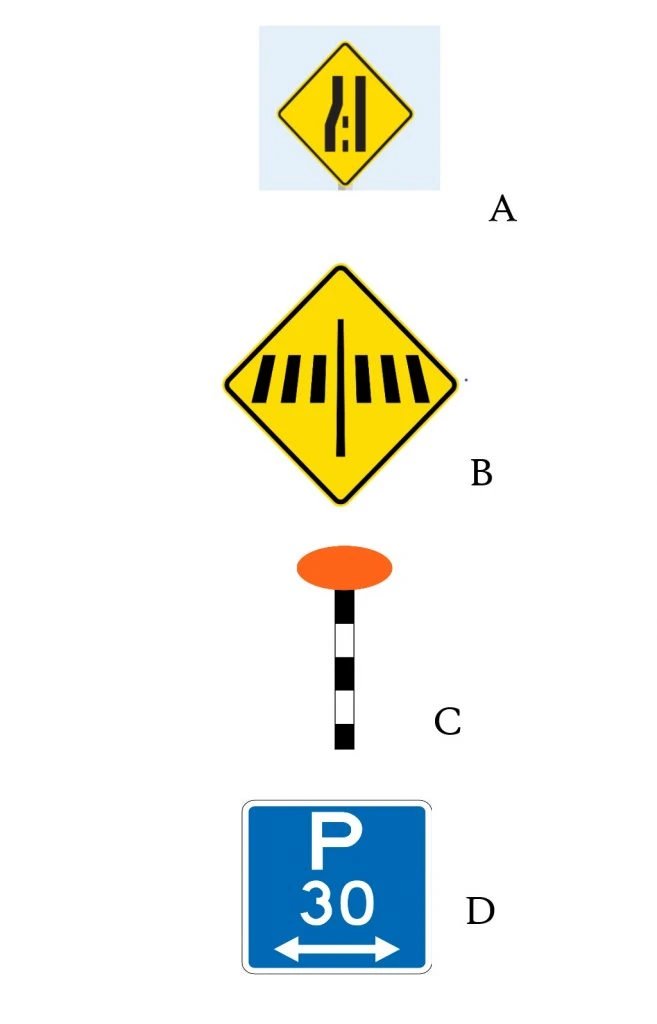

You don’t get handy “merge ahead” signs. Instead, you get Sign A in the diagram below. The idea is to “merge like a zip”, left-right-left-right, etc.

Pedestrian crossing (zebra crossing) signage is different. The familiar sign with the pair of walking legs isn’t on the zebra crossing itself, and you don’t get the zigzag road markings leading up to the crossing. Instead, you get the warning sign (Sign B), with an orange dot on a stripy pole on the crossing (Sign C).

Pedestrian refuge islands aren’t signed. This means that at any time a centre island divides two lanes of traffic, there could be a lurking pedestrian hoping to cross. Keep your eyes open (and the pedestrian will be doing the same). Refuge islands with designated cut-downs for pedestrians are common near roundabouts.

Parking limits are in minutes, not hours. If you got all excited about a sign saying “P5” or “P15”, believing that you’d be able to park there for 5 or 15 hours, I’m sorry to disappoint you. You’ve only got 5 or 15 minutes. If you’re lucky, you can find signs giving you 90, 120, 180 or 240 minutes of parking (if you look hard enough), meaning 1½ hours, 2 hours, 3 hours and 4 hours, respectively. Sign D is a typical example.

If you’re in an urban area, the speed limit is probably 50 km/h. There aren’t as many 60 km/h sections. Local traffic areas don’t exist, so assume that it’s 50 km/h unless told otherwise.

Even on the motorway, you won’t get to go 110 km/h legally. At the time of writing, the Kiwi Powers That Be are discussing the introduction of 110 km/h sections on some main motorways. However, this is still in the discussion stage, so if you head over this winter, you’ll have to keep your speed to a maximum of 100 km/h when in rural areas.

School zones don’t have the times handily displayed. If the signs are flashing, the reduced speed limit (either 30 or 40 km/h) applies; if they’re not flashing, the usual speed limit (usually 50 km/h) applies.

Speed cameras are sneaky. Permanent ones – and there are some – don’t have warning signage. There have been calls from lobby groups to introduce signs warning you that there are permanent speed cameras in position, but there aren’t any yet. You may, however, see some signs warning you about red light cameras. NZTA has taken to calling both speed cameras and red light cameras by the twee name of “safety cameras” but the majority of Kiwi think this is a cringeworthy attempt to not call a spade a ruddy spade. The NZTA Journey Planner website has a map showing you where the mobile ones are, so check this when you plan your journey (it’s a good idea to check it even if your right foot isn’t on the heavy side, as it will also tell you if roads have been closed or if there are major roadworks underway).

Witches’ hats everywhere. The roading contractors just LOVE witches’ hats and will put up heaps of them even weeks before the actual road works take place, and these will probably be the last thing they take away. They’ll also start appearing up to 1 km ahead of the road works (in rural areas). They’ll also put up insane numbers of the things. I have no idea what they’re thinking. Do they think that if there’s a car-sized gap in the middle of a long row of witches’ hats that I’m going to decide to cross the line? Incidentally, not many Kiwis will use the word “witches’ hat” but will call them a “road cone”. Near universities, you may spot some in unusual places, such as up trees.

Campervan Conversions And #VanLife

It’s perfectly possible to sleep in the back of most cars in a pinch, as long as the rear seats fold flat and you have a reasonable bit of padding underneath you and a pillow (speaking from experience here). However, I wouldn’t want to do it for more than a night or so in a row without very good reason. If you like to stay in campgrounds or in the middle of nowhere but don’t want to lug around a caravan, then possibly the answer is to build your own campervan, giving you more versatile motoring as well as the ability to take secure accommodation with you – and making it easier to find a park when you stop in to pick up supplies.

If you want to convert a vehicle to a campervan, you need to start with the right one. Vans are always popular and give you more floorspace and headroom in your mobile bedroom, but it’s also possible to convert a sizeable SUV or MPV.

Good vans for converting to a campervan include:

- Mercedes Sprinter (a popular choice for many enthusiasts)

- Ford Transit

- Fiat Ducato

- Toyota Hiace

- Hyundai iLoad

- VW Crafter

- VW Kombi – the classic retro campervan!

Good SUVs and MPVs for conversion are:

- Toyota 4Runner

- Toyota Estima

- Honda CRV

- Honda Odyssey

- Skoda Octavia

In fact, any decent-sized SUV or van or MPV can be converted into a campervan. Even some utes with a covered deck can be used as campervans. Some can even be converted into full legal motorhomes, as long as you meet the standards.

The simplest way to convert your vehicle into a campervan is simply to fold down the back seats, then toss in a mattress, a butane stove and some picnic plates, and you’re good to go. You may also be able to even remove the rear seats completely, although whether you can do and have a legally roadworthy vehicle will depend on which state you’re in.

Assuming that you can remove the rear seats permanently (or at least until your holiday’s over), then you can go one step further and build a bed platform, which will avoid the problem of weird niggly bumps under the mattress that will make you realize where that folk tale of the Princess and the Pea came from. The advantage of a bed platform is that you can store stuff under it (like your clothes and your cooking gear).

If you want more than a place to sleep and a place to stash clothes and food, then you can add all sorts of things. LED fairy lights and rechargeable batteries have made lighting a lot easier than it was when I was in my 20s, so don’t worry about installing fancy lights unless you’re super-keen. The upgrade that a lot of people like to go for is a loo of some sort; in fact, if you’re a New Zealander reading this, you have to have some sort of loo on board to get certification as a freedom camper. I’d add curtains as one upgrade, as cars and vans are usually built for visibility, which means that when you’re trying to sleep or get dressed inside the van, you’re still exposed to the outside world. Even if you are in the middle of nowhere and get changed in the dark, the light of the rising moon can still wake you up in the wee smalls (although an eye mask or a beanie pulled over your eyes can do the trick).

Ultimately, exactly what you want to put into your vehicle to convert it to a campervan will depend on what you want to do with it and how long you’re going to be doing it for. If you are currently without a permanent home and living the van life, like one of my nieces did, then something larger will make your life more comfortable. The big thing to remember, as with any DIY project, is to measure first and play around with squared paper (or a computer-aided design tool if you know how to use one) before you head down to Bunnings and start cutting up the timber.

To be legally classed as a motorhome in Australia, the vehicle has to be fitted with seats and a table, which need to be fixed (although fold-down tables are legit); storage (fixed), somewhere to cook (also fixed) and somewhere to sleep, which also – you guessed it – needs to be fixed. It also needs good ventilation and a fire extinguisher, and you need to stick with the weight restrictions for the class of vehicle. If you want to add anything fancy involving electricity, water or LPG gas, then this needs to be professionally installed and certified for your own safety as well as to meet the requirements. You can read the full requirements here.

You can also take the easy option and simply add a rooftop camper to a ute or 4×4, which takes out a lot of the hassle of cutting, measuring and shocking the neighbours by what you say after hitting your thumb.